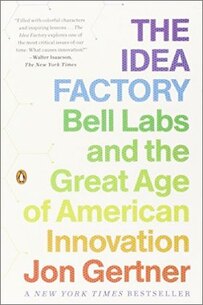

The word innovation gets used so much today that it has lost some of its meaning. But there is no doubt that what Bell Labs embarked on for 75 years in the last century to bring about universal connectivity was innovation. To achieve their mission of bringing universal connectivity, Bell Labs had to innovate in so many areas that they had to create a factory of generating ideas. The history of Bell Labs innovation is explained well in the outstanding book Idea Factory: Bell Labs and the Great Age of American Innovation by Jon Gertner. He writes about the times when Bell had the attitude, mission, talent, leadership, resources, and perseverance to make breakthrough innovation happen. Bell Labs had the Innovation Dream Team of researchers, scientists and engineers to create the information age that we live in today. Gertner brings the heyday of Bell Labs to come alive when it was the place to be to do great research. Bell Labs did it by creating an innovation culture that lasted until they achieved their core mission of bringing about universal connectivity. Soon afterward, Bell Labs started losing its edge through divestiture, acquisition and competition. Nevertheless, we can learn a lot about innovation from Bell Labs and avoid the mistakes that led to its decline and eventual demise. In this blog post, I pose five questions to Jon Gertner about lessons we can all learn from Bell Labs. I am very thankful to Jon for answering these questions I had after reading his great book. A hallmark of a great book is how many questions it raises in your head. On a personal note, I worked at Bell Labs for a couple of years in the early 1990s. It was a fun place to work since there was so much you could learn by being around smart people doing amazing things. But it was also quite frustrating since you could see their culture was getting in the way to make necessary changes to compete with emerging players. The frustration of working at Bell Labs in the 1990s was summed for me when I once asked a veteran Bell Labs employee, what was the best thing to ever come out of Bell Labs? He caustically answered, "Ex Bell Labs employee." I liked Gertner’s The Idea Factory a lot and started reading his new book The Ice at the End of the World: An Epic Journey into Greenland's Buried Past and Our Perilous Future. This recent book looks at the melting ice sheet in Greenland that could be pointing toward climate change taking place. I am sure I will have a lot of questions from reading that book. You can get more information about Jon and his books at jongertner.net. Five Questions Question 1: Do you think Bell Labs lost its way since there was no unifying mission after they fulfilled their mission of "universal connectivity" set in the early 1900s? I was at Bell Labs in the early 90s, and they were doing a lot of interesting stuff. But since there was no overarching mission and purpose, the projects went nowhere. Eventually, other-focused players picked it up and turned it into a huge business. These days, I think corporate "missions" are taken lightly — seen, probably correctly, as a kind of rhetorical marketing ploy, rather than a real attempt to define the parameters and direction of work. But I do think Bell Labs was somewhat different in this regard. Remember, it was still an R&D lab for AT&T, a much larger corporate entity. And from the 1920s onward, AT&T's goal of "universal connectivity" gave the Labs its mandate in terms of technological development. At the same time, the research group within the Labs hewed to the idea of defining "the future of communications." In tandem, these ideas were powerful. They shaped the work done at the Labs up until the breakup in the 1980s. In my view, AT&T's goals were specific enough to keep scientists and engineers focused on the potential utility of their ideas; meanwhile, Bell Labs' research mission was broad enough to encompass almost any kind of physical, chemical, and electronics experimentation. In the years after universal connectivity was achieved— which, depending on your metric, can either mean just around the time of the breakup (with fiber optics, radar and satellite communications, and trans-world cables coming into service) or somewhat later (when mobile phones began to scale up)— there's no question Bell Labs lost part of its mandate. How to implement the disruptive ideas that the scientists were working on? The world was already connected; the marketplace was already crowded with a number of telco companies that could move very fast. And I think there's a good argument that at that point human and data communications became commoditized, meaning the goals of companies became the pursuit of better and cheaper technologies, gaining market share, and raising penetration rates. That was not what Bell Labs was good at. And as a result, its relevance began to erode. Question 2: As you point out in your book that it required tens of thousands of engineers and scientists over 75 years to create the age of information. Do you think with machine learning, breakthroughs today have to be delivered much faster with a handful of scientists and engineers with lot less money? Without question, we're in a faster world, and organizations are leaner and increasingly reliant on machines, rather than men and women. Certainly, we've all heard that before. But I tend to worry about how easily we toss around words like "breakthrough"—it can obscure the difference, say, between a commercial breakthrough, which can no doubt be important in many respects, and an engineering or scientific breakthrough, which can be meaningful on a much larger scale but sometimes commercially disappointing, at least in the near term. I think one of the most important aspects of the Bell Labs/AT&T monopoly was that it afforded the company's staff extraordinary amounts of time—decades, really—to develop breakthrough technologies in switching and electronics, without having to commercialize them too fast. Very few big companies of today can do that, perhaps only Google or Apple. And with the latter, we're talking about companies that are focused on ideas that help them to gain or maintain market share, which is different than what Bell Labs was doing. I think one could make the argument that breakthroughs—scientific and engineering breakthroughs, that is, which dramatically change our lives the way telephones and transistors and lasers did—can now be achieved faster with machine learning and AI. And fewer people. This sounds like it might be true. But I'm not yet sure we've yet seen significant impacts from this, whether it's in the field of communications, material science, or medicine. I'm open to hearing otherwise. Question 3: Do you think the thirst for innovation-to-market is slowing down or even preventing, tackling difficult problems? One good thing about a big problem is that it doesn't go away. If a company focuses on a make-do solution that doesn't work or rushes out something substandard that fails, someone else will try to do better. Assuming the problem involves potential revenue, it will always have suitors. But sure, I think the easy money—smaller problems, and especially small and lucrative problems—makes VCs and corporate strategists look in the direction of making things happen fast or focussing on challenges that are easy rather than hard. I'm not sure, though, what the remedy for that would be—except for changing the role of government and public investments in R&D. And I think that's definitely something to consider. For now, the innovation-to-market rush certainly makes academic research, and national laboratory research, more important, assuming the ideas arising from those environments have a path to transition into the market too. It also makes the forays of near-monopolistic companies like Google and Facebook more important. Question 4: Do you think the skill set needed to be an innovator is different today than what was needed when Bell Labs existed? For example, the innovation leaders of recent times have not been scientists such as Steve Jobs, Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, Bill Gates, etc.? Well, I think our media environment and celebrity culture is now focused on CEOs—making them somehow seem responsible for all the innovations within their companies. It's kind of preposterous. We all know the managers and techies under these business titans do the real work, and it's work that's often remarkable and innovative. There were (and are) innovators working under Jobs and Bezos who probably resemble a lot of the technical staff at Bell Labs. And certainly, I could see Bill Gates or Paul Allen working in the Labs’ computer group, tinkering with UNIX, if they had hit the scene 10 years earlier. As for Elon Musk, well, that's more complicated. He is an impressively knowledgeable engineer with tremendous ambitions; he certainly would be smart enough to have been a Bell Labs recruit. But I imagine he would have chafed in that corporate and genteel environment. It would have been too constraining. He would have done something outrageous and left in a huff. Question 5: What can innovative companies learn from Bell Labs, so they don't meet a similar fate? Is this even possible? It's a difficult question, in that Bell Labs existed at a very different moment in time. It can serve as an example to some companies or organizations of today—especially ones aiming to make true engineering and scientific breakthroughs—but probably not others that are doing rapid and incremental innovations to serve a specific and fast-changing market. That said, if there is one overarching lesson from Bell Labs, it's that world-changing work is created by extraordinary people working together in close contact on difficult problems. Also, those people need a degree of autonomy and resources commensurate with their talents and ambitions. That sounds generic, but I don't think it is. And it sounds simple, but I don't think it's that, either. Sometimes I think the focus of many startups and founders, especially those driven by the VC ethos, is on the wrong things—how lean the company is, for instance, or how strong the promotional department. Not that those aren't important. But if you're trying to do something really extraordinary, there can be hazards to leanness and to market-driven pandering. At any rate, I don't think the goal of any company should necessarily be to repeat the Bell Labs example. Rather, it's to seek what is useful from this place and see how it fits into a new paradigm. In my book, there are a lot of ideas—about people, management, workplace organization— to pick and choose from. Five Book Recommendations The Making of the Atomic Bomb, by Richard Rhodes The Metaphysical Club, by Louis Menand The New New Thing, by Michael Lewis The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, by Thomas Kuhn The Sixth Extinction, by Elizabeth Kolbert #####  Jay Oza is a writer, speaker, executive coach. He makes people thrive on high stakes stage whether it's for a job interview, a sales presentation or an important speech. He is the author of the book Winning Speech Moments: How to Achieve Your Objective with Anyone, Anytime, Anywhere. Please download the speech checklist and the speech workbook to help you with your next high stakes speech. Please contact him if you would like to have an two 75 minute coaching session for $499 or invite him to your location give a talk on Interviewing or High-Stakes Speaking. You can reach him at [email protected] or 732-847-9877.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorJay Oza Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

© 2017 Winning Speech Moments

RSS Feed

RSS Feed